-

The Economics of Burnout in Healthcare

Care for our fellow humans cannot, of course, be reduced solely to figures or numbers. However, we are in the midst of a burnout epidemic in healthcare across the world and it may help us to acknowledge the seriousness of this point in time with the aid of an economic analysis.

We all hear daily of the delays in being able to see a GP, the shortage of GP’s, excessive waiting times in ED, elective surgery blowouts, record rates of nurses leaving their profession, shortages of staff – the list goes on. But often the stories seem to come so incessantly that they blur into one and go unheard.

And what of burnout? The occupational affliction that contributes, at least in part, to all of the problems above and also is related to poorer physical and psychological health (including increased suicide rates) in the person suffering. Can we assign a dollar cost to this condition?

For the sake of these calculations I have used data from the US and extrapolated some to an Australian context. Please remember that the numbers may not always be accurate in any transfer, but the themes will be similar and, of course, the exact figures are not the most most important takeaway – more that we have an urgent call to action and an opportunity to improve healthcare systems for the benefit of us all.

- There are 340,000,000 people in the USA

- It is estimated that 100,000 people in the US die each year from medical errors (Rodziewicz, Houseman, Hipskind, 2023) and that these errors occur in both inpatient and outpatient settings (Rodziewicz and Hipskind, 2018)

- It is known that doctors suffering from burnout make twice the rate of serious medical errors compared with non burnt out doctors (Shanafelt, Balch, Bechamps et al, 2010).

- Assume approximately 50% of doctors in US affected by burnout (conservative estimate – most studies indicate higher rate of burnout)

- Therefore, of the 100,000 deaths we can assume that 66,000 are made by doctors suffering with burnout, and 33,000 by doctors unaffected by burnout.

- Every US citizen has a 0.029% (roughly 3 in 10,000) chance of dying each year from a medical error, however that goes up to 0.039% (around 1 in 2500) if treated by a doctor suffering with burnout, and down to 0.018% (less than 1:5000) if you are treated by a non burnt out doctor. I guess we all want to get the doctor unaffected by burnout, huh?

Annual expenditure related to medical errors in the US is approximately $20 billion (Ahsani-Estahbanali, Doshmangir, Najafi et al, 2021) – which equates to $59/person/year just to pay for medical errors.

In Australia, if the same cost applied to medical errors/person applied, this would equate to $91 AUD, with a nationwide bill of $2.37 billion AUD for our 26 million populace.

Imagine that we could eradicate burnout in the, let’s say, 50% of Australian doctors affected. This group would make half the errors and save $788 million each year.

That’s a lot of money. Of course, it is somewhat abhorrent to think that saving money could be more motivating than reducing human suffering and death. And these calculations do not take into account the poorer teams that result from doctors with burnout, the overall reduced standard of care, nor the costs on the doctor’s own health and that of their families.

Make no mistake – we know some of the causes of burnout, and we know that certain demographics such as young doctors are more affected. It is clear that burnout can have its genesis in medical school or early career years. We know some of the organisation-level changes that can help – such as reduction of unnecessary or duplicated clerical and bureaucratic load. We know that improving teams and culture reduces burnout. We have wellbeing science that informs many of our individual interventions.

So, with all of this information at our disposal – and with significant potential fiscal saving as well as reduction of human suffering – why is it that we are not doing more to prevent, combat, and treat burnout? Why aren’t our organisations and institutions engaging with the science to reduce the precipitants of burnout? Why aren’t we prioritising how our teams function and optimising organisational culture? Why aren’t we engaging with evidence-based interventions and measurement? Does there have to be an even greater cost exacted before we address this problem?

-

Known Certainty

Recently, I met a coaching client for her second session. As we greeted each other it was immediately apparent that her energy and mood had shifted from the first session. She seemed lighter, her shoulders were higher and posture straighter. There were smiles instead of tears.

In the initial session, we had talked about pressures and expectations. It became clear that these were largely internally generated. Like many doctors, this person had uncompromising expectations of herself.

Perfectionism involves an underlying anxiety tendency, as well as a need to be certain – to be right.

As we had completed the first session, we had discussed taking a different approach. Looking at things from another perspective and deriving self-worth from internal measures as opposed to perceived external feedback. In addition, we commenced a gratitude practice and a type of breathwork.

At the second session the doctor announced that the first meeting had “changed her life!” While this was a wonderful affirmation, I wondered if it could be true. Could a single session really change someone’s life? Would that change be maintained, and did it need to be? Or had the slight nudge in trajectory already set her on a different and more fulfilling path?

In medicine and health, we implicitly learn that it is important to be, and appear, certain when dealing with patients and others. We therefore consciously and unconsciously cultivate an image of being all-knowing. Not encompassing doubt.

Accuracy and confidence is, of course, critical in so much of healthcare. But could an over-reliance on certainty sometimes lead to negative consequences for ourselves and our patients?Excessive over-certainty could lead to embedded inflexible attitudes and a type of naive realism – where our own view of the world is believed to be the only reality.

When these rigid attitudes and beliefs become pervasive, often at the stage of being a junior doctor, they may allow for a degree of comfort with less self-doubt and fear. Indeed, adopting this mindset may be adaptive, as it reduces the need for cognitive resources to be diverted to consideration of unpredictability or uncertainty.

But does this benefit patients? Does it limit our own positive emotion and creativity, and does it reduce our ability to visualise alternate possibilities and different futures? Does it mean that we overcommit to a particular diagnosis and treatment?

This fixed mindset, perfectionism, and need to be right could lead to less empathy for our patients. It could result in giving a ‘factual’ and harsh prognosis without allowing for the unknown, or indeed the unknown unknowns. It may lead to less hope for the patient and family – and we know that once hope is lost, clinical outcomes deteriorate.

As the parent of a now-adult child with a significant life-long diagnosis, I have met with multiple specialists. Some have given the the bleak textbook outlook, devoid of any positives. This has left me feeling deflated, defeated, and helpless. What is the point of going on? I have also dealt with doctors who have acknowledged that even in a difficult situation, none of us can truly know the future. Even in an awful situation, we don’t know exactly what can happen.

These doctors manage to retain their authenticity and recognise the challenges, but still allow for a degree of hope. I know which of the above doctor’s attitudes that I prefer. Hope is energising – it enables you to take forward steps and continue to battle.

So, could this image that we cling to – of being right, certain, perfect, all-knowing – the attitudes that we unconsciously associate with a ‘superior’ doctor, also lead to a single viewpoint and an inflexible attitude?

A circumscribed way of being, and a limited range of allowable emotion with over-reliance on suppression as a form of emotional regulation, may not be in the clinician’s best interests either. A rigid thinking pattern, need for certainty, and emotional suppression, are implicated in burnout. Especially when we reach the point where there is no joy in our work.

What would be the effect of adopting a different lens, seeing alternative viewpoints, acknowledging other perspectives? Would it lead to less individual certainty in one’s own world? Would it lead to loss of credibility as a clinician?

Or would the reverse occur? Would you generate positive emotions, feel happiness, allow your patients to have increased hope, and become a better doctor with a broader scope and increased ability to connect?

These seemingly-simple attitudinal changes may be able to create powerful positive outcomes. Perhaps discussion of, and thinking about, how one thinks, really is important and necessary for us all.

Maybe facilitating broader perspectives and enabling a wider range of attitudes really can change a life.

-

Leadership in Healthcare

All people will experience leadership or being led at times during their life. Whether this be in the school yard or in a board room, we have all had leaders in our groups and teams. Many of us have been the designated leader. Given that leadership is so ubiquitous, seemingly we’d all have a clear understanding of what makes a good leader. However, like many of the most important elements in organisations and society, leadership is poorly understood.

Leadership is felt at the unconscious and emotional level rather than evaluated cognitively. We ‘know’ when we are being led well or badly. Good leadership needs to include technical competence and proficiency with the prevalent systems but must also encompass factors that are only experienced intuitively.

The emotional measures of leadership, such as how much trust the group places in the leader, have become neglected and undervalued. Perhaps these elements are diminished because they are less visible and harder to evaluate and comprehend. However, the emotional aspects of leadership are some of the most critical. These factors must come to the fore and be examined and developed if our systems are to change for the better.

What is Leadership?

When I was first starting to be appointed to leadership positions within medical teams and hospital departments, I felt some anxiety. Who was I to direct and control these groups of educated and high-performing individuals? I started to research leadership theories and practices to improve my capabilities and alleviate my anxieties.

From the multiple shelves of books on leadership in any bookstore, it became apparent to me that leadership is a highly valued but poorly understood topic. I also found that there were many different approaches and answers to the question about what leadership consists of. Many of these bookstore texts, often written by an individual who had followed an unconventional path to success (which often also included becoming outrageously wealthy), asserted that their method was the only recipe to achieve your goals. However, none of them seemed to hold the secret to my leadership challenges. While all of the books contained insights and interesting anecdotes, it appeared that each organisational or group context would be different and require its own approach.

As well as edicts from billionaires, many of these leadership books were written by military leaders, detailing actions in battles and wars that were then somehow extrapolated to peacetime business situations, or leadership in other fields. This felt disingenuous when thinking of organisational leadership. A business or hospital is not at war with its competitors. Most of the messages didn’t seem to apply. I wasn’t at war, beginning a start-up, or concentrating on amassing a fortune. Despite the multitude of conflicting ideas, I didn’t really apply any of the lessons learned from the leadership texts.

Oddly, I found that some of the best outcomes that I had with my team would be when I used techniques or styles of behaviour that were similar to those used when playing or coaching sports. The groups responded to being cared for in similar ways. It wasn’t so much control or detailed direction that was required, more so care and respect.

The medical teams needed to connect with each other just as much as a group of teenage athletes playing a sport did. The kids played better when they were treated with affection and allowed to have a sense of fun. The doctors performed for higher stakes, but also worked more effectively when they had a caring and enjoyable environment. It wasn’t about controlling them – it was about relationships and guidance.

The realisation (which perhaps should have been obvious) was that there isn’t a secret way to lead specific teams. All teams are the same, in many ways. The first factor to create a great team and culture is as simple as being nice to people and treating them fairly and respectfully with clear communication. The doctors didn’t want me to tell them how to do their job, they just needed a supportive framework around them where they could develop trust and feel part of a team in which there was regard for all members.

The Desire For Leadership

It is obvious that leadership roles are desired and prized by many in our society. People gain power with leadership roles in any setting and associate such roles with enhanced status and often increased remuneration. As humans, we have an unconscious mental shortcut that assigns other abilities to those in powerful positions, frequently assuming that due to their high status in one field, their opinions about unrelated topics also somehow have extra authority. Therefore, there are many reasons and attractions to leadership. People with certain personality characteristics – including narcissism – will be drawn strongly to leadership roles, even when they are poorly suited.

Each of us has an image or construct of the ‘ideal’ leader, ranging from an authoritarian figure who can bravely lead us forward through solo action and decision making, determination, and self-will, to the democratic leader who involves and consults many people before making each decision.

Leadership is a complex concept that encompasses many facets. It may sometimes be easier to consider what it is that leadership is not than to define what leadership actually is. Leadership is not just the job title, the position, a particular set of attributes, or an ability to organise and manage. Some of the areas encompassed by leadership include: setting cultural expectations, communicating, motivating, collaborating, directing, delegating, taking ownership of difficult situations, taking responsibility for poor outcomes, inspiring others, dispensing consequences, recognising noteworthy efforts, giving directions, making sense of uncertainty, strategising, collaborating, expressing gratitude, forgiving, counselling, and supporting.

Further, leadership is about directing focus onto areas that need or deserve attention. These may be organisational goals, improvements, corrections, or modifications required, as well as areas that warrant praise due to unusual or unprecedented success, exemplary effort, and behaviours valued by the organisation. The leader must have the requisite skills for the position within the appropriate industry and must have clearly held personal values which are congruent with the desired culture of the organisation. The leader must also have an ability to create and share goals with other members.

When I think of the consultants, directors, or heads of units who influenced me most during my training, I must wrack my brain to discern who gave the best advice on surgical technique, or who I obtained certain theoretical knowledge from. However, I have immediate recall of how I felt with each of my ‘bosses’, and what emotions they stirred in me. Some of the lessons I learned were from those I didn’t want to emulate. The best learning was from those whose behaviour I admired. These people were kind, not only to patients but to juniors, nurses, and all staff. I felt great affection for these leaders, and I worked harder for them as I was determined not to let them down. When around good people, we behave more virtuously, with the opposite also applying. The best leaders – those I wanted to be like – were honest, kind, and fair.

As leadership research increases, it is more frequently recognised that emotional intelligence correlates with leadership effectiveness. This does not just imply nicety, but also kindness, empathy, an ability to register the emotional states and needs of other people, and a willingness to try to assist. These qualities are part of the rich mix that constitutes wisdom. Wisdom implies a level of intelligence, both cognitive and emotional. It also requires self-regulation of emotions, which allows the use of different and appropriate styles of interaction according to circumstances and the people involved.

Wisdom has long been recognised as an important virtue in a leader, with both ancient Greek and Chinese philosophers having similar sayings along the lines of, ‘With power must come wisdom’.

The current challenges to hospitals are causing many organisations to consider their culture and try to increase organisational pride, foster staff well-being, and produce a flourishing environment. This is more than merely trying to continue with a current strategy, or business as usual, which only requires technical management or transactional leadership. These hospitals are also examining their leadership structures.

Evolving into a thriving organisation requires a more inspired transformational leadership style that engages the emotions and imagination of staff. This is where curious, appreciative leadership prioritises development of people over development of building or organisational processes. In this environment egos can be controlled in order to collaboratively create the desired vision. With this style, the leader does not need to control everything. They are more responsible for helping to unify, envision, and facilitate. The leader does not have, or need to have, all the answers. The leader encourages a vision and invites others to collaborate with the detail. In this structure, a leader will be content helping to trace an outline and stepping back to allow others to add the colour.

The Secret to Becoming a Leader

When many of us rise in seniority and start to assume leadership roles, we follow the same path. We read leadership guides and manuals, we watch TED Talks, we explore the importance of performing a daily ‘twenty-mile march’,[i] try to become more effective by establishing ‘seven habits’,[ii] and suppress hunger while we are ensuring that we ‘eat last’.[iii] We try to begin with understanding our ‘why’[iv] and attempt to ‘lean in’.[v]

These are all inspiring messages with outstanding lessons. But reading a book or having a position title does not make one a true leader. We may consider ourselves the leader, but can someone really be described as a leader if they don’t have committed followers? Without followers, or at least colleagues who are collaborated with and consulted, perhaps the real position description is organiser or manager. Staff do not choose to be led or become followers because of which books someone has read. They listen to and line up with those they trust and feel affection and respect for.

Perhaps we don’t need the books. It may be better to just reflect on how our own memorable and treasured leaders have treated us in the past. In some ways, we already instinctively know what is required, if we are brave enough to admit it. Deep down, we all know how to look after others, build mutual positive regard, and help create happy and functional teams.

The mentors and very best leaders that each of us has been associated with created a feeling of nurturing, and a sense of being understood. There were, of course, non-negotiable areas relating to performance standards and behavioural guidelines, but even these were learnt in an overarching framework of kindness. To give these gifts to others will be to get them back. The leader in title, who treats others with affection and care, will become the leader with devoted followers.

Excerpt of From Hurting to Healing – Delivering Love to Medicine and Healthcare

Author: Simon Craig; Hambone Press, 2023.

-

Transformation of Organisational Culture

In many organisations we hear of the desire for ‘transformation’ or ‘transformative change’. This seems to imply a longing for a kinder, more collaborative environment where increased prosocial behaviour is exhibited. Essentially, the term refers to a better place to work. This desired transformation relates to improvement in organisational culture.

What is Transformation?

Transformation is strictly defined as a radical change in appearance, configuration, or shape. To move from one form to another – such as a caterpillar metamorphising into a butterfly. But does transformation have to involve alteration of external appearances? And does it have to be complete – if only some elements of the object in question change is this still transformation?

Many publicly-funded organisations, when given a grant to enable architectural change or new buildings, seem to assume that this new look will transform the organization. That the changed external appearance will somehow alter all of the internal workings, including the culture. Unfortunately, in many settings, despite a new shiny building, a poor culture remains – to the great dismay of staff.

In this setting, transformation must also relate to a change in the character or inner essence of the organisation. To truly transform, an organisation must also alter its culture with shifts in how people understand, interpret, and carry out their roles and relationships. Within this cultural transformation will be increased feelings of belonging, pride, and affection towards their workplace.

Belief in the Possibility of Transformation

Most of us are beguiled by the possibility of transformation in both a personal and broader sense. The fascination with inspiring change and progression to elevated states is reflected in art, literature, and movies. We love a ‘rags to riches’ tale, or a heroic story of succeeding despite overwhelming odds. In these scenarios the change, or transformation, is often preceded by significant challenges. A period of self-reflection and marshalling inner strengths then leads to overcoming adversity. Adopting positive attitudes and rediscovering resilience allows the protagonist to become more creative and find novel ways to solve the problems they face.

Even as children, these messages are delivered – that we can overcome adversity through determination, dedication to the cause, and courage. We learn that while the process will be scary and hard, it is what we must do.

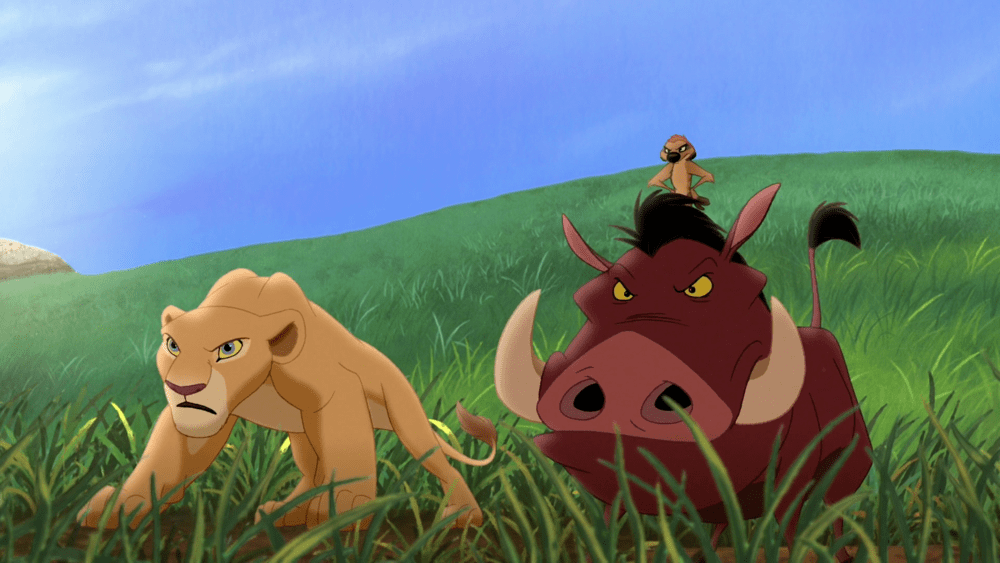

In Disney’s ‘The Lion King’, the wise King Mufasa had been killed through the actions of his evil brother Scar, and Mufasa’s cub and heir, Simba, had run away due to fear and misplaced guilt. Eventually Simba grew into an adult lion, with an altered appearance. Importantly, he also chose to confront his fears in a desire to help others in the now-neglected kingdom. Simba overthrew Scar to bring about much-needed change that enabled the kingdom to flourish once more. The transformation of Simba paralleled the regeneration of the land and natural order.

Snow White had fallen into an everlasting sleep through eating a bewitched apple and was cared for by her friends – the seven dwarfs. The dwarfs looked after her in the comatose state for years until eventually Snow White was awoken by “love’s first kiss”. Of course, it was fortunate for Snow White that the kiss was delivered by a handsome and wealthy prince! Snow White awoke, physically transformed into a lovely (and conscious) princess.

Are there lessons that we can learn from these fairy tales? The obvious moral is that even when our circumstances are dire, transformation is possible. Enduring commitment to a noble cause, while not simple or easy, can eventually lead to a positive outcome. Perhaps when change occurs, sometimes things can turn around quickly.

The other learning to take from movies such as the hugely popular Lion King, is that all people are energised and motivated by virtuous goals. All of us want to live in flourishing environments and all will support courageous leadership that holds noble aspirations.

Are the organisations with poor culture simply ‘sleeping’? Can they be awoken with commitment to positive change?

How Do We Start to Transform Our Organisational Culture?

In many aspects of life, the oldest wisdom is the best. It has stood the test of time, and the fact that it remains means it has intrinsic truth that still resonates. So we can learn important lessons about change from philosophers through the ages (just as we can learn from cartoons!).

Just starting to think about organisational culture change can make all of us feel trepidation. Why is that? Because change is hard, and you will face resistance and opposition. It will take courage. You won’t overcome the fear – that will continue. It’s courage that allows you to persist despite the fear and anxiety.

Courage isn’t having the strength to go on. It’s going on when you don’t have the strength. Napoleon Bonaparte

So, we think we have the courage and desire to go on and create transformational change. The first step will be understanding the current situation. Defining any issue in the greatest detail guides the process and even starts the solution. Therefore, what is our cultural problem?

Again, courage is required because we will have to face up to, and surface, assumptions and attitudes that we have been suppressing. We need to admit unhelpful behaviours of our own that we haven’t dealt with. This will be a confronting, yet necessary, step.

It is only when we accept who we are, that we are capable of change. Carl Rogers

But wait! The poor culture….that’s not my fault!…that’s everyone else, isn’t it?

No – it’s all of us. To get culture change means that we all have to understand our own part in it, our contribution to the present state of affairs, and our role in improving things. If we want to see change it has to start with us (yes, we have all heard this one before)

Be the change you want to see in the world. Mahatma Gandhi

What Can I Do?

Yep, this is the point where everything usually falls down. Where the initiative splutters to a standstill. It’s right now that we start to tell ourselves the usual stories: that it’s up to the leader; it’s up to the ones who are causing trouble; it’s up to those that never do anything; I have tried before so it’s not up to me; it’s up to someone else to start…and then I’ll follow.

Get the idea? Does this sound familiar?

Again, if we want change then it’s up to all of us (and please note: everyone is anxious and scared – not just you)

We hear the refrain, “It won’t work! We’ve tried this before!”

Well…if the same techniques and initiatives have failed so many times before, should we give up?

No! Let’s do it differently this time. Let’s combine the wisdom of the ages with the transformation we see in movies, and that we long to believe in.

We can start by imagining what each of the characters in the fairy tale cartoons could do to change the systems they operate in (and we will imagine them in a role in a present-day organisation).

Simba (emerging leader) – often these people are immobilised by fear and doubt when faced with the need for culture change. It’s hard to overcome the resistance and negative voices. Without Simba being brave the negative conditions are not challenged.

So, the Simba’s of the world need to do what they instinctively ‘know’ is right. They can have trust that others will follow their lead. Rather than think about all the current organisational restraints, or all that is wrong, they need to imagine what the group could become. Their positive view of an alternative future will galvanise others to support their dream.

It isn’t what you look at, it’s what you see. Henry Thoreau

Scar (current leader of failing system) – These leaders will have a tendency to deny the problems and resist change. They may feel that through admitting change is required they are viewed negatively and blamed.

The Scars of the world avoid admitting that previous decisions were poor. These individuals have to understand that part of achieving wisdom is through admitting mistakes. They cannot let their own ego and hubris get in the way of leading for the good of all.

If unable to develop self awareness and exhibit integrity, Scar may need to step aside for the benefit of the organisation.

If you do not change direction, you will end up where you are heading. Lao Tzu

Mufasa (wise elder of the team) – Their greatest days may be past them, but don’t underestimate the value of experienced and balanced mentors. Their words, lessons, and behaviours resonate widely. Others will model on these people creating an ongoing effect for years after they have left any group. This lasting effect must be a positive ongoing influence.

A society grows great when old men plant trees in whose shade they shall never sit. Ancient Greek Proverb

Timon, Pumba, Nala (the quiet achievers and leader’s supports) – these may be the unsung heroes. These are the people who support emerging leaders and changemakers. These are the people who keep the positive messages going at the start of the process – when the pushback is the most fierce.

Being loved by someone gives you strength, while loving someone deeply gives you courage. Lao Tzu

Snow White (disillusioned staff member) – despite suffering in the past and pulling back, the Snow Whites of the organisation must become enthused to commit again. They must realise that when it feels right, the initiative will need everyone’s energy.

Even though exposure to some bad apples has left them dejected, injured, or isolated, the Snow Whites must regain enthusiasm and become part of the solution.

When we are no longer able to change a situation, we are challenged to change ourselves. Viktor Frankl

The Snow Whites can learn further from Frankl, and and understand that what they have endured over the years has given them strength and shown their resilience.

Without the suffering, the growth that I have achieved would have been impossible. Viktor Frankl

Seven Dwarfs (the coal face workers – turning up every day without complaint) – it is up to the organisation to recognise and thank these people. Organisational leaders that do not appreciate these individuals can subsequently have more workers becoming disengaged and suffering with moral injury.

Without these people, the system would have shut down. Their actions every day are essential and through these acts they have a quiet dignity.

Moral excellence comes about because of habit. We become virtuous by doing virtuous acts. Aristotle

The Prince (the changemaker) – We can all be this person. Every seemingly small action can have big effects. Each ripple creates change.

One small domino on its own seems insignificant, unless it’s the one that can start the whole cascade of assembled dominoes.

The people who are crazy enough to think that they can change the world, are the ones who do. Steve Jobs

If we try hard enough we can resurrect a failing organisational culture.

We have to believe that transformation is possible.

Imagine a new way. It won’t come solely from the actions of one person – it will need input from all.

-

Appreciating Disengaged Workers

In most organisations disengaged workers are viewed with disdain by leadership. They are seen as being a blight on the workplace, flawed troublemakers, and somehow morally reprehensible. Disengagement is felt to be due to an inherent problem with the individual concerned.

However, the disengaged worker can be viewed in an entirely different way – a way that allows understanding of these people and the challenges they have faced and which may lead to improved outcomes for the workers and the leadership.

An alternative view of disengagement

A high rate of disengagement in workplace survey tools is feared by organisational leaders, as it is a public indication of poor organisational ‘buy-in’. The immediate reaction is a desire to silence these voices. But the disengaged workers may be those who once entered the organisation with the highest hopes and the most optimism for what they, and the organisation, could achieve. They may be the people who most fervently believed in the words of the organisation’s mission statement.

Those who have the greatest emotion invested can be the ones who are most vulnerable. These people are sensitive to thwarted goals and hopes. They can be the ones who get damaged the quickest. The trauma may include moral injury or burnout.

In this way, disengagement can be a defence mechanism. Rather than being let down once more it’s easier to become closed off and cynical. Instead of showing enthusiasm for a new organisational structure or management plan, one’s instinctive reaction may be seen to be obstructive and negative.

But these workers may be the proverbial canaries in the coal mine. These individuals may be the ones more easily affected by a poor working environment. Their disengagement may point to a workplace that has suboptimal conditions or culture, that will eventually affect others.

So, instead of reviling these people is it possible to somehow appreciate what they may be telling us? To drill down on their frustrations and listen to what has lead to the disengagement. Important insights may arise that give organisational benefit. Ironically, willingness to listen may begin the process of repair and engagement.

Leadership and Disengagement

We all recognise that leadership is difficult and a subordinate who is a pebble in your shoe can quickly become a major annoyance. In a busy world it may be easier to disregard, or even terminate, a worker who has continual gripes or doesn’t show a level of enthusiasm that is seen as being appropriate.

A different way to view these people may be to consider that their personal hopes, or dreams for how the organisation would develop, have not been realised, and that they have suffered heartache over this. Bringing an attitude like this may allow compassion and understanding. There could also be significant challenges in this person’s life outside work. Sometimes we have to walk in another’s shoes.

In some situations the disengaged worker may be too far along the road to be able to reimagine committing to the organisation’s purpose, and it may be more appropriate to part ways. However, this should not be a hasty decision for these workers are often vastly experienced and carry a wealth of organisational knowledge.

Whatever the final outcome, leaders must listen to disgruntled workers. Even in a critical commentary there will be some rare gems of unfiltered truth – which unfortunately are often discarded as the feedback is uncomfortable to hear. Again, true leadership is hard and it requires courage. Those brave enough to listen, and willing to consider inconvenient viewpoints, may be able to create change that ultimately benefits all within the organisation. Dialogue with disaffected workers may represent an opportunity, even a gift, for a struggling organisation.

Can disengagement be reversed?

If disengagement sometimes constitutes a defence mechanism to protect the worker from having their hopes dashed once more, then engagement may equate to faith and belief.

Belief that the work is important and that the leaders always have the best interests of workers as part of decision making. Faith that the organisational directions are noble. A belief that the words of the mission statement are an ethos that drives all actions, rather than just ink on paper. Disengagement might be the point when faith is completely eroded.

Can disengagement be reversed and can faith be restored? I don’t know if it’s always possible, but I do know that it starts with qualities such as listening, compassion, humility, and integrity.

-

Healthcare Teams

-

Improving Strategic Decisions in Healthcare

Why is it Difficult for Doctors and Administrators to Agree?

A problem within our healthcare systems is an often-unrecognised divide between senior administrators/executives and the doctors caring for patients in the very same organisations. Why is this, when all have the best interests of the patient cohort and the institution at heart? What can be done to achieve more understanding and collaboration?

The roadblocks can arise from the way the two groups are trained and how each profession approaches decision-making processes. The obstacles are usually overcome, but resulting in both sides feeling aggrieved. However, occasionally the disagreement can turn into an unhelpful impasse.

If each side understands the other more (and indeed if each side has a greater understanding of themselves), then perhaps the misunderstandings, frustrations, and outright battles can be converted into more collaborative outcomes.

What Influences How Doctors Develop Their Negotiating Style?

In our healthcare system, doctors progress through a competitive environment where individualistic practices naturally come to the foreground. Rapid and decisive thought patterns are valued and uncertainty in action is not. Each doctor will ascend some way through the ranks of a hierarchical and conservative culture reaching higher status (and becoming an advisor or possibly ultimate decision maker). This hierarchy leads to resistance in accepting guidance or opinions from those of lower status.

The medical enculturation and promotion of self-belief, perfectionism, and need to appear all-knowing, can lead to ingrained assumptions where the doctor believes that they know better (or could do a better job) than others in different positions or professions (including executives).

When doctors are involved in group decision making they focus on the outcome, irrespective of the journey taken to get there. Immediate action is valued, after the doctor believes that the correct course is clear and that a decision has been made. Delays at this point create significant frustration for doctors, and these delays can be interpreted as deliberate and disrespectful to their already-invested time.

What Executives Value and the Place of Bureaucracy

In the decision-making process administrators pay great attention to the process. The bureaucratic process relies on canvassing all relevant opinion and seeing a problem from multiple viewpoints. This is , necessarily, a slower initial path, but it can be argued that this style will save later holdups due to previously overlooked factors. The strength of bureaucracy is to look at all issues from different angles and have a more complete understanding of the problem, and avoid neglecting or overlooking any important information.

The weakness of the bureaucratic process is that it is lengthy to the point of potentially becoming bogged-down, with the subsequent loss of the enthusiasm needed to drive the process of change.

Executives will attempt to think in a total-system style which considers patients as a collective, whereas doctors, unsurprisingly, will find it difficult to separate any proposal from how they perceive it affecting individual patient treatment.

Styles of Negotiation

Different negotiating styles between doctors and administrators can also cause obstacles. In any relationship or negotiation an individual can take one of four approaches:

- Competition (I win/You lose)

- Accomodation (I lose/You win)

- Compromise (Lose/Lose – both accept some reduction in position)

- Collaboration (Win/Win)

Unconsciously, and perhaps related to personality type, training, and adoption of medical culture, doctors almost invariably negotiate with a competitive win/lose attitude. When faced with a weak or seemingly losing position, the doctor will default to a lose/lose approach. None of this is surprising when one considers the competitive nature of medical training and practice. However, becoming aware of our own assumptions, behaviours, and challenges may allow us to create a better decision-making pathway.

Strengths of Each Group

Leading into any important decision-making, planning, or negotiation process it is important to recognise the strengths of each group and the value in each approach. Doctors are good at reaching decisions quickly after assessing all currently available information and committing to action. Of course, over many years, doctors often have to bear sole responsibility (including litigation risk) for any patient’s outcome. This obviously influences attitudes and decisions.

Administrators are good at creating inclusive decision making that allows unseen or unappreciated risks and viewpoints to surface, and thereby avoid poor decisions due to haste or lack of breadth in the process.

With greater understanding of seemingly opposed viewpoints, and acknowledgement of our own cognitive styles (with their strengths and challenges), perhaps we will be able to move to a more frequent collaboration between the groups that leads to benefit for all.

-

Turmoil in Healthcare

It seems that every aspect of life as we know it is currently changing.

Of course, rapidly evolving climate change with altered conditions, more-frequent natural disasters, and flow-on economic consequences and climate refugees, will increasingly effect all of our lives.

However, many other elements of our lives and society are also shifting. These include:

- an increasing wealth disparity, lack of fairness, and segmented society

- increased political polarisation – perhaps most-obviously seen in the US with the ‘red/blue’ divide

- Far right extremist political parties, movements, and attitudes in many countries

- Lack of trust in leaders – political and business

- Low birth rates and aging populations in developed countries

Many of these changes seem to have come on quite quickly. But most actually occur slowly, almost invisibly, for some time until they are recognised. Similarly, in many countries of the Western world, systems that have lasted for generations seem to be stretched and failing. This includes Healthcare. Some of the manifestations of our failing health system (due to unrecognised long term change) are the erosion of general practice, unprecedented demand on Emergency Departments, reduced healthcare worker wellbeing and skyrocketing burnout levels.

These indicators of a struggling system have not arisen overnight and are not solely due to the Covid pandemic. Instead, they have come about silently, almost imperceptibly, over many years until they ‘suddenly’ become a pressing issue. Perhaps this is inevitable. All things, including social systems, decay over time – particularly when overlooked, taken for granted, or neglected. And all systems, including the mode of healthcare, eventually become obsolete and are replaced by other systems.

But before one system can be replaced by another stable system there will be a period of turmoil that includes instability and uncertainty. As humans, we dislike feeling unsettled and we resist change. We prefer the familiar than the unknown. Change comes with fear and anxiety. Routine patterns are comfortable and require less cognitive effort.

However, in many systems including healthcare, this period of turmoil can be appreciated rather than resisted. This is the time that delivers potential for needed change, even rebirth, and can be used to great effect. When we accept the inevitable degradation of our systems, and instead recognise the opportunity for improvement, we can let go of fear and resistance to change. Rather than trying to maintain things exactly as they are, we can approach the new dynamic with curiosity and optimism about creating better systems and better ways.

Health organisations, teams, and the overarching bodies that have an ability to guide societal healthcare delivery systems, are all important to this process. All have a role to play. Acknowledging current challenges and deficiencies will be crucial to allow acceptance and recognition of opportunity. Those who can develop hope and enthusiasm about the future will direct change in more positive ways than those who are motivated through fear or an inability to imagine a new paradigm.

Guiding positive change can regenerate healthcare and enable better integration of all facets of our system. Positive change can further create a collaborative environment that optimises desired results while also prioritising communication, inclusion, and facilitation of the wellbeing of staff and workers.

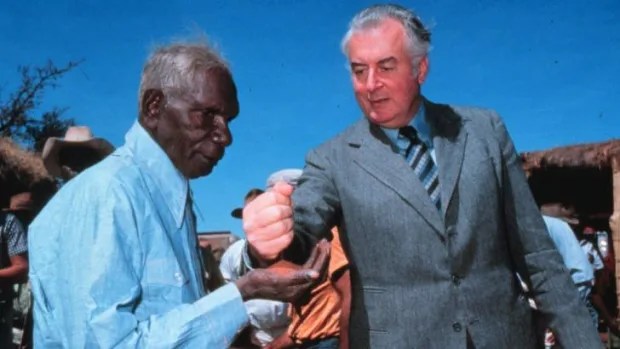

In many ways (and to paraphrase ex-Prime Minister of Australia, Paul Keating), perhaps this is the turmoil that healthcare needed to have.

-

6.5 Strengthening Bonds

The importance of leadership feedback cannot be overestimated.

Kindness, balance, support, and wisdom are essential qualities that a

team needs from its leaders; without them, a group will not excel. The

leader must recognise and appreciate what each team member brings to

the group, and ideally this is spoken about and disseminated publicly.

‘Praise in public, challenge in private’ is a useful phrase to keep in mind.

However, of equal importance in generating a highly cohesive group is

enabling the team members to appreciate each other.

At the end of 2021, as the Covid-19 lockdowns and restrictions were

easing in Australia, it became clear that our obstetric department team

could meet in person as a group for our usual December celebration.

These dinner meetings were always eagerly anticipated, however, this

year, I hadn’t had time, or indeed inclination, to arrange any

presentations. In fact, the very thought of arranging another meeting left

me with an overwhelming sense of exhaustion. I asked the group whether

we should go ahead with the event, secretly hoping that they would

decline. However, there was great enthusiasm to meet and have dinner

and the usual fun night, so I booked our regular venue.

When the date rapidly arrived, with growing trepidation, I had come up

with only one activity. This would be an activity that was unfamiliar to

most of us, including myself. My sense was that it would either be a

roaring success or a complete disaster. After the usual end of year

comments, I stood in front of the group of around 50 doctors and senior

midwives holding a container full of individually wrapped chocolates.

“In this bucket, I have three Lindt Chocolate Balls for each person” I

began, “The first is for yourself. This is to recognise all the hard work that

each of us has done, and the resilience that we have shown after a tough

couple of years. So, the first chocolate for each person is to honour

themselves” – I paused and then continued, “The other chocolates are to

give to two other members of our team. These are for special efforts that

you have noticed, to express thanks, to acknowledge hard work, or to

publicly appreciate someone who has gone above the usual excellent

standards to do something amazing. The only proviso is that we each

come to the front and present our chocolates, telling everyone what the

recipient has done that is special.”

I presented my own two gift chocolates, one to a junior doctor who had

been struggling with the pressures of work but had lifted her effort. With

persistence and dedication, she had become a reliable and valued

member of the team. The other I presented to an extraordinary senior

midwife who was a wonderful leader. She combined efficiency and

compassion to both staff and patients in an admirable mix. I stepped

back.

There were some moments of quiet. I sensed a reticence to be the first

to participate in the process. Finally, just as the silence was becoming

uncomfortable, a doctor rose and came to the front. Taking chocolates

from the bucket, she presented thanks and chocolate to two others in the

group. Soon after, the enthusiasm for the activity became infectious.

Some wanted to present a second round of chocolates. Eventually, every

member of the team had risen, one by one, and thanked, recognised,

appreciated, and honoured, others in our team.

There were affirmations given that night which were heart-warming.

There were comments and anecdotes that I had not heard before, and

perspectives I hadn’t considered. In the end, all of us seemed to be aware

of how fortunate we were to belong to the group. We felt joint pride,

mutual respect, and gratitude. With the team’s ability to be brave and

open on that night, many bonds were strengthened.

From Hurting to Healing – Delivering Love to Medicine and Healthcare. Hambone Publishers, 2023.

-

How Do We Create a Team?

Some teams appear to come together effortlessly, while other groups

cannot seem to coalesce even with major interventions devoted to

the task. The process of forming functional teams can be one of the

hardest tasks within an organisation. Becoming a successful team happens more easily when members establish good communication patterns and acknowledge the qualities and abilities of colleagues. At that point, a common purpose seems achievable. But, although it sounds very straightforward, the

unfortunate reality is that teams that are both happy and successful

are uncommon. This is not due to mutual exclusivity of these two markers, but because excellent teams are rare. Therefore, outstanding teams must be cherished and further examined for clues around what it was that allowed the group to coalesce.Perhaps, rather than a hospital team, we should consider what is required in the formation of a successful sporting team. Within sports, success is more easily defined, and the necessary ingredients appear more visible. Sports teams rarely achieve success without unified commitment to a team goal and positive regard for all teammates. Overly individualistic self-focus, or a dominant ego, weakens the team ethos.

Medical groups can be a little like high-level professional sports

teams. Most of the individuals are talented operators with great skill

and self-belief. Each group of doctors will belong to a team or unit

that has joint responsibility for many patients. Within this structure,

however, are also many instances of individual decisions or actions

that a particular doctor can take. These outcomes, for instance with

surgical procedures, can also be easily tabulated and analysed, as

can the overall departmental data. Cricket seems to be the sport that most closely parallels specialist medical teams within hospitals. As previously alluded to, while a cricket team consists of 11 team-mates, in some people’s eyes the

team is actually a group of 11 individuals. Players are judged on

their individual achievements (such as runs scored), and the team’s

total score is cumulative of each player’s individual tally, rather than

coming from joint team achievements. Indeed, each delivery bowled

is essentially a one-on-one contest. Within the construct of the sport

of cricket, individual statistics are highly scrutinised.However, many of the greatest bowlers of all time, the highest

wicket-takers, largely operated in tandem with a particular bowler

from the other end. This other bowler was not as successful in terms

of wickets taken but played a different role. This ‘less-successful’

bowler kept pressure on the batsmen through tight reliable bowling

which restricted run-scoring. The build-up of pressure from slow

scoring often led the batsmen to take more chances against the star

bowler and resulted in them losing their wicket. In this instance, who

deserves the glory? The wicket-taker? Or the bowling partnership? Or perhaps the fielders who saved runs, also generating pressure? Tight fielding, saving runs, and taking catches all add to team success.Within a hospital, who deserves recognition? Should it be the surgeon performing an operation? Attention could also be directed to the role played by the anaesthetist maintaining the patient’s oxygenation and life support while anaesthetised, or the theatre nurses handing the appropriate instruments at exactly the right moment. There is also the critical role of the GP who first diagnosed the problem, and the dietician optimising the patient’s nutrition status to facilitate healing. Clearly this list goes on. There is obviously a large group of people, constituting a complex system, involved in every episode of care for each patient. The overarching goal of the organisation is for the patient to be cured, to heal, and to recover. The system by which patients receive care requires the input of many individuals with different complementary skills. What is the term that we use to refer to this system? Most would call it a team. Just as with sports, medical team success is dependent on many factors and many people, not just one. If any of the roles are not performed well, the outcome is less successful.

Returning to the cricket analogy, what if the team is not united

but still has several established world-class performers? Recognised

champions or stars who make the newcomers ‘earn their stripes’

before begrudgingly accepting and integrating them into the team.

In this scenario, an inexperienced player who does not feel valued

will be more nervous, and therefore will most likely not perform

at the peak of their abilities, perhaps leading to a dropped catch.

However, in a team where a young player is immediately accepted

as a full member upon selection, with their qualities recognised, the

debutante will feel more relaxed and possibly able to stretch a little

more, enabling a difficult catch to be taken. Another wicket for the

star bowler, and the resultant outcome of team success.A saying often heard in youth sports is, ‘There is no ‘I’ in team’, which implies that one’s own agenda and desire for personal recognition should be set aside and the team goals be considered paramount. While this may be true in team sports, is it so in medicine?

If we consider medical teams in a similar light as a cricket team,

perhaps the most venerated surgeons, for example, would be the

‘high-flyers’. Within this environment, like cricket, if the whole team

is not performing optimally and smaller steps are missed, it impacts

team success. And then the most vaunted performers will be at risk of

poorer outcomes for their patients. Unfortunately, within medicine,

there can be an external sense that self-interest is causing individuals

to compete against other members of their own team. This reduces

success for both the individuals concerned and for the collective.Perhaps a better saying that allows for individual goals and striving for personal excellence while still recognising the need for tight and supportive team bonds and an overarching desire for group achievement is:

“The strength of the wolf is the pack,

and the strength of the pack is the wolf.” -

Some lessons about organisational culture learned from picking up dog shit.

Recently I moved suburbs. Where I used to live everyone seemed to carry plastic bags when walking their dog. All owners picked up their dog’s droppings. There was very little dog shit on the nature strip or footpath.

I assumed that my new location, a more affluent place with big houses and expensive cars, would have even better standards with owners cleaning up after their animals. To my surprise this was not the case. In the rich suburb, there was much more dog shit laying around for others to step in.

Lesson 1: More impressive surroundings does not guarantee good behaviour or better culture.

Walking Lily, my dog, each day in the ‘leafier’suburb, I now noticed owners who would openly ignore the shit their dog left in public places. Some would pretend not to notice their dog taking a dump, while others reluctantly would pick up the pooh, but then hide the full bag under a tree or leave it on top of someone else’s fence as though it was another person’s responsibility to put in the bin.

I became upset with these behaviours, but over time I also started to hesitate when Lily took a pooh. If no-one else picked up after their dog – why should I? Why should I carry a steaming bag of excrement around with me?

When Lily paused, arched her back, and started to strain, I began to surreptitiously look around, to see if anyone had noticed my dog doing her business.

Lesson 2: In poor cultures, new members may initially become disillusioned with suboptimal practices, but will eventually adopt similar behaviours which become unconscious and unquestioned.

In the first suburb there was a communal park where dogs could be off the leash. At this park were a number of outlets that dispensed dog-pooh bags, provided by the local Council. These bags were accessed and used by all. In addition there were bins handy to deposit the full bags in.

Lesson 3: To generate optimal behaviour the overarching organisation must make the desired action easy. When the desired behaviour is convenient, simple, and frequently seen, it becomes the norm. The underlying assumption held by the group is that all do the right thing.

During the Covid lockdown, services were reduced and the free bags at the park were less often replenished. However, despite this, the good practices continued. Local residents began carrying their own bags from home and still picked up after their dogs. The amount of dog excrement lying around did not increase.

Lesson 4: When good culture is well established it will overcome times of difficulty. Good behaviour will continue.

Today, in the newer suburb, I still carry bags with me and I pick up every time. Often I have to uncomfortably carry the filled bag for some time before finding a bin. Why do I do this? Why carry an uncomfortably warm bag of pooh around when no-one seems to value this?

I guess it’s because even when no-one else cares whether or not I have done the right thing – I still know. The influence that I have in this practice of neighbourhood cleanliness is over my own actions, rather than other people’s.

Lesson 5: Good cultural practices must start with each individual.

Happy dog-walking!

-

Is Strategy a Healthy Breakfast?

Photo by Burst on Pexels.com Optimising Healthcare Culture

There is a famous saying in business circles that is attributed to American management consultant Peter Drucker: “Culture eats strategy for breakfast” (1). This glib pronouncement does not mean that businesses, including healthcare institutions, do not need operational strategy. Rather, it denotes that if there are significant issues or poor performance within an organisation, cultural improvement should be preferred over alteration of strategy. It also implies that the best strategy will not count for much in an environment with poor culture. Indeed, a good organisational culture often negates the need for many strategy initiatives, as creative solutions to problems often arise and are implemented organically.

We have discussed the difficulty of defining, assessing, and understanding culture. But strategy is different – it is more easily understood, more visible, and better defined. Most definitions of strategy are something like, ‘A long-term plan for achieving a goal or a result.’ Within these words is the key to the difference. A plan is the result of a cognitive process has been thought out, and the goal or results are defined end points. Culture is sensed instinctively, and any changes, good or bad, can become embedded over the longer term with ongoing effects.

When considering the idea of strategy, we understand that it can be communicated, written down, and thought of as a linear path to success. Strategy is superficial, visible, and controllable. It is a process that has clear timing of implementation, and easily measurable success or failure. Strategy involves mechanistic change. Culture change is more organic. A change in culture will involve processes that are deeper, less visible, and more mysterious. To create successful culture change is harder but more permanent than strategy implementation, as it is part of the evolution of the organisation. Strategy change involves what an organisation does; culture change involves what an organisation becomes.

[1] Drucker, P. F. (2020). The essential Drucker. Routledge.

This is an excerpt from the book From Hurting to Healing – Delivering Love to Medicine and Healthcare (2023). Hambone Publishing. https://amzn.asia/d/ffBkIUp

-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.